The above image is courtesy of Tread Media and was first published here.

In Part 1 of this series on monitoring training load, we wrote about incorporating external load (i.e. power based metrics). The focus of this post is integrating internal load metrics (with external metrics), to understand athlete progression, recovery, and readiness to perform.

As cycling grows in popularity and professionalism, understanding and managing training load is more critical than ever. Although power meters and their metrics are now widely adopted by athletes, ranging from recreational to professional, many coaches and self-managed athletes continue to overlook basic training principles.

To truly understand an athlete’s response to training, internal load metrics, such as rating of perceived exertion (RPE), heart rate (HR), and subjective wellness scores, should be integrated into a holistic monitoring approach.

Build a Holistic Picture of Wellness & Athlete Fatigue

At Science to Sport, one of our fundamental coaching principles is to recognise that training load is not merely what is done (external load), but how the body responds to it (internal load).

From the author’s Instagram & courtesy of Specialized Factory Racing.

What is Load Monitoring

Training load monitoring is the synthesis and analysis of either internal or external variables. These may be either directly or indirectly related to, or affected by training. The point of monitoring is to balance stress and recovery to optimise performance while minimising illness or injury.

Historically, coaches relied on observational cues and athlete self-reporting, but by the time an athlete reports feeling tired or weak, it’s often already too late to prevent performance decline or injury.

Today, a data-rich ecosystem allows for more refined monitoring, yet interpreting this data meaningfully remains the challenge. The concept of load must be dissected into external load (the work done) and internal load (the physiological and psychological cost of that work).

External Load Metrics

Power output has become the gold standard in cycling for quantifying external load. It is

- objective,

- reproducible,

- unaffected by motivational or environmental variables.

From the author’s Instagram – seen here field testing the structural integrity of his bike.

Common power-based metrics include:

- Training Stress Score (TSS),

- Chronic Training Load (CTL),

- Acute Training Load (ATL),

- Training Stress Balance (TSB).

These measures allow coaches to visualise training trends, anticipate periods of peak form, and flag overreaching. However, they do not account for individual variability in stress response, recovery status, or environmental stressors (e.g. heat, altitude, travel).

Internal Load

Internal load metrics provide crucial insight into how the athlete is coping with the imposed training load.

Internal Load Metrics

Subjective Wellness & The Submaximal Fatigue Test (SFT)

We have put together a separate how-to explainer here, detailing how to implement the S2S Submaximal Fatigue Test protocol.

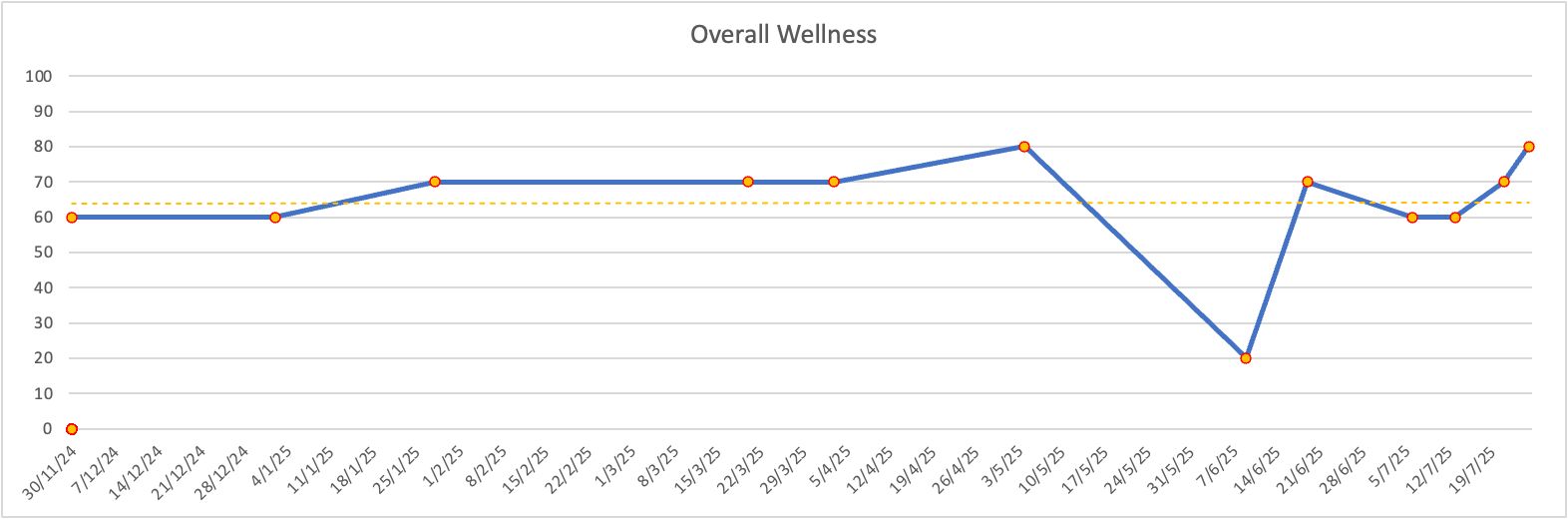

How we integrate load monitoring at Science to Sport

S2S Coaches integrate weekly subjective wellness, and/or a submaximal fatigue tests (SFT). Our subjective wellness comprises of only five simple questions. We document:

- Fatigue

- Sleep

- Stress

- Mood

- Overall feeling

We previously used longer, validated questionnaires (such as the DALDA), but found that the difficulty in obtaining consistent feedback from anything beyond a few targeted questions outweighed the potential benefits.

Once feedback is quantified, we flag responses outside a given standard deviation. These flags often appear before performance is affected, and addressing the flags early is an important step in managing any athlete.

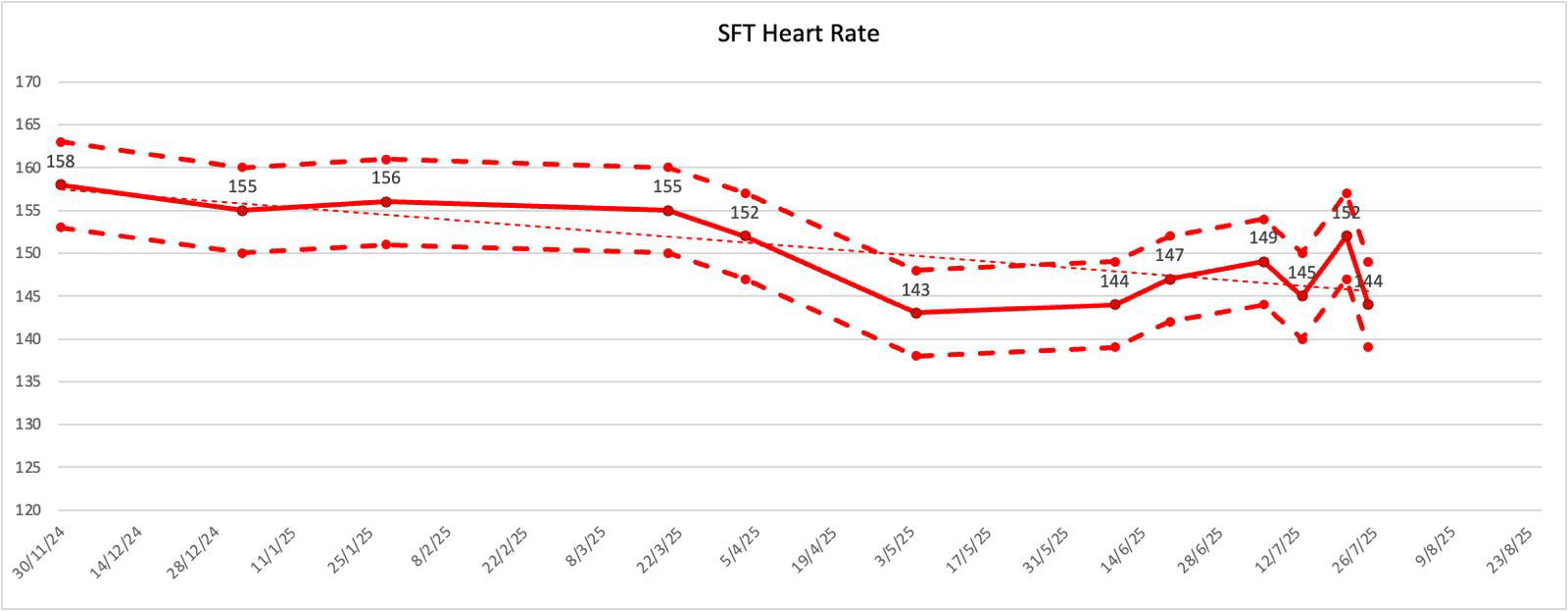

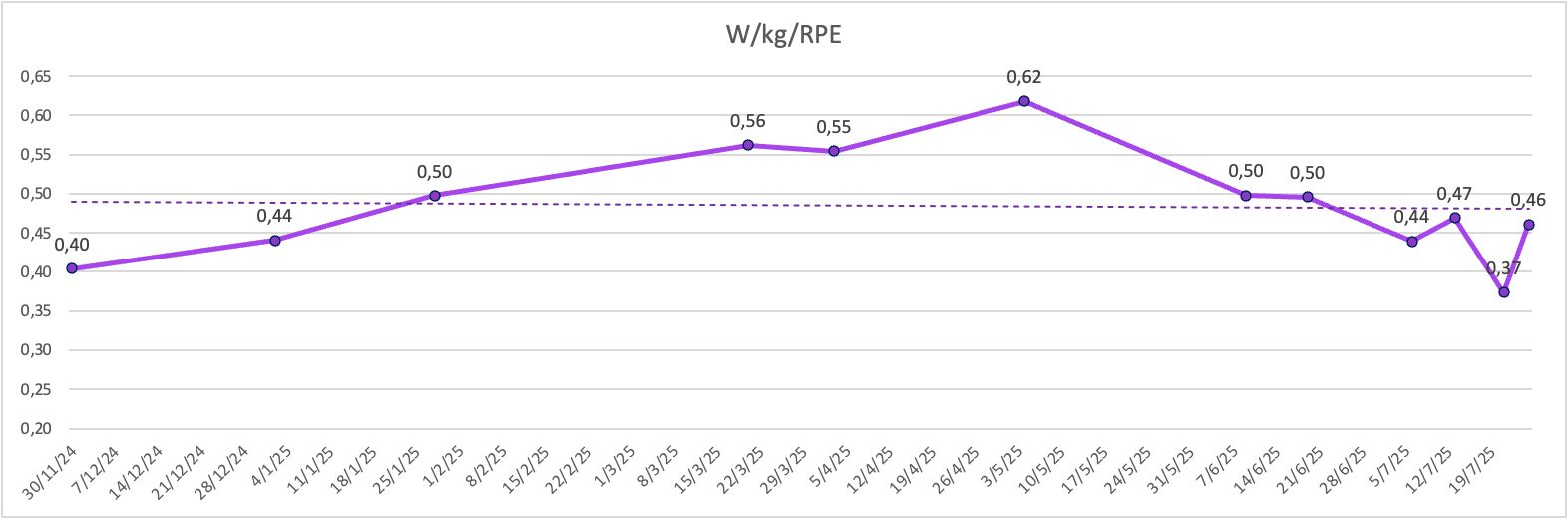

How S2S implements our Submaximal Fatigue Test

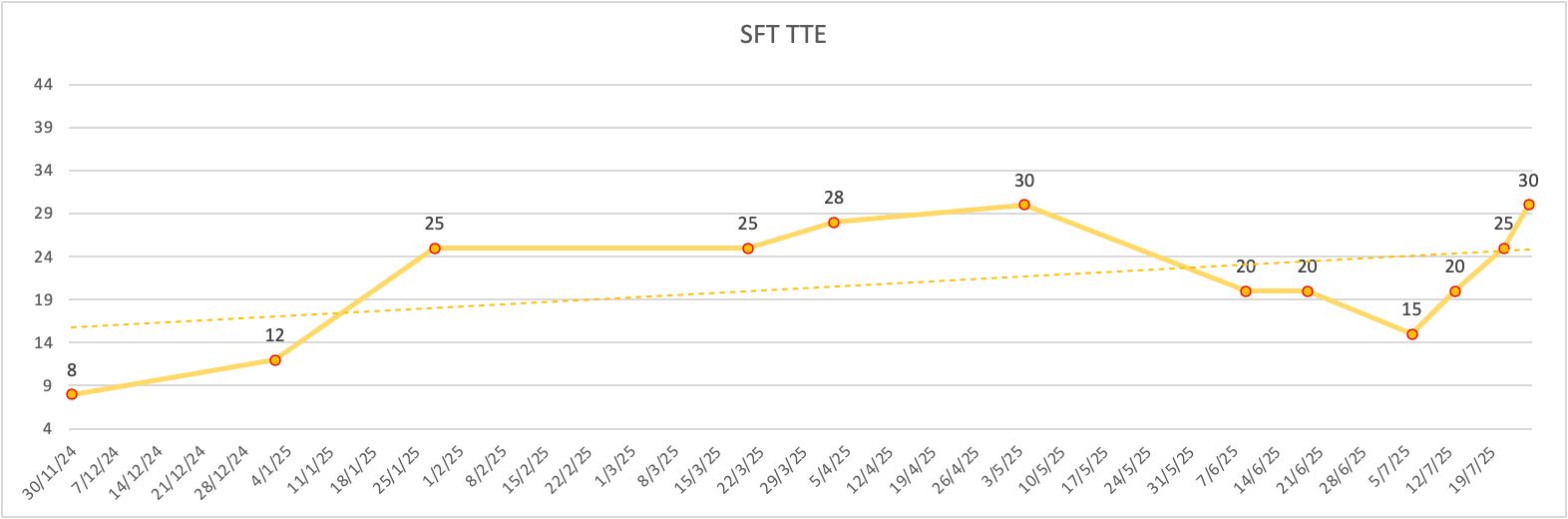

The SFT test is designed as a non-invasive submaximal performance test which can be included regularly, with minimal added load and stress to the athlete. The test is short and relatively easy to do: simply hold a moderate-to-hard effort for 3 minutes.

This effort is standardised at 110% of FTP (Functional Threshold Power). FTP is the power an athlete can sustain for a prolonged duration (approximately 45-75 minutes).

After the 3 minute effort, the athlete reports their exertion on the original Borg RPE Scale and reports how long they felt they would have been able to hold this power (Time to Exhaustion; TTE).

By triangulating:

- power,

- perceived exertion,

- heart rate,

we get comprehensive insight into an athlete’s performance and potential signs of over-reaching.

When the athlete reports perceived exertion, they also complete the same five subjective wellness questions. These are often critical in giving the coach the full picture of an athlete’s wellness and levels of both mental and physical fatigue.

SFT Tracking Data

Click any chart to view full size

Why Subjective Metrics Matter More Than We Think

We recently performed a study (currently unpublished data), where we investigated the sensitivities of these different parameters. Subjective Wellness Data and Internal metrics (RPE and TTE) were able to predict 7 Day-TSS, ATL and TSB, but not CTL.

As expected, the external load metrics with the greater sensitivity to acute fatigue, had the greatest ability to be predicted. Simple subjective questions, and perceived effort during the SFT predicted nearly 20% of the Training Stress Balance (TSB).

Among the five questions, by far the most meaningful question was simply to ask the athlete “How fatigued are you feeling” in the last 7 days.

We also tried to identify if changes in performance can be predicted from:

- Subjective Feelings

- External Load Metrics (TSS, ATL, CTL and TSB)

- Heart Rate

We were able to predict 21% of the variance in performance. Again, the simple question: “How fatigued are you feeling” in the last 7 days, was by far the most meaningful component of the algorithm.

Putting It All Together

No single metric will ever tell us the complete story. We need to understand the underlying physiology and use the external and internal load metrics to understand the full picture. A robust monitoring system triangulates these inputs to make informed decisions about training progression, recovery needs, and readiness to perform.